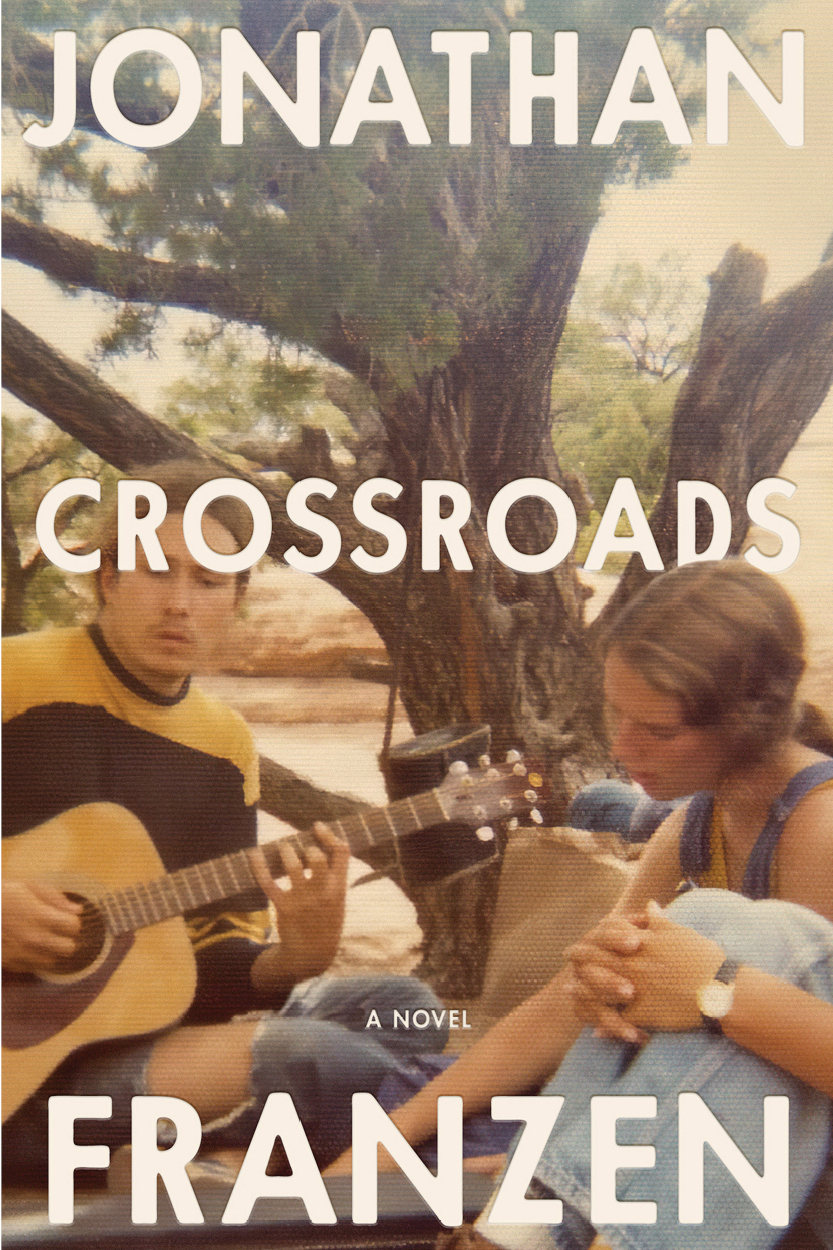

This time, though, the journalistic impulse was more intrusive, especially in an improbable subplot about strip mining in West Virginia. His next novel, Freedom (2010), was at its considerable best as another mid-Western family saga.

Yet these were rare missteps in a novel that went on to sell around three million copies and to establish Franzen, in the words of a celebrated Time cover, as the latest “Great American Novelist”. In its more transparently journalistic moments, the book did contain a few fossilised remains of his former news-bearing ambitions. Franzen’s all-conquering third book, The Corrections (2001), anatomised a mid-Western family, not unlike his own, in a way that managed to be unsparing, tender, funny, melancholy, dense and page-turning all at the same time. The consequent change of direction certainly paid off. His problem, he decided in a 1996 essay, was falling for the idea that “I should Address the Culture and Bring News to the Mainstream” rather than embracing “my desire to write about the things closest to me, to lose myself in the characters and locales I loved”. Both were politely reviewed, serious-minded explorations of contemporary America.

By the mid-1990s, he’d published two novels, The Twenty-Seventh City and Strong Motion. It’s hard to imagine now, but Jonathan Franzen was once a struggling author.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)